When we attend a production or premiere of an opera of our time there are several issues to consider: Is the work good? Does it have the quality or enough elements to survive in the future? Is it possible for a 21st century opera to be part of the repertoire? The answers are not simple and provide much food for thought.

Although Brett Dean’s “Hamlet” draws on Shakespeare, it is an opera of its time, not a literal staging of the work of the great English bard (We even get the famous “to be or not to be” lines from the beginning) As valid as an example of today’s musical art as was Ambroise Thomas’s “Hamlet”, premiered in 1868 and practically the only opera based on “Hamlet” that has remained within the fringes of the repertoire; with 19 performances in 5 countries in 2022 versus Dean’s 7 “Hamlet” performances in 2022, all in New York.

Dean’s “Hamlet” was composed between 2013 and 2017, premiered in 2018 in Glyndenbourne, England and has been heard in other cities including Adelaide, Australia, the native country of the composer and Nicholas Carter, the conductor who has been in charge of the recent series of performances of this work.

As is often the case with contemporary opera, the backbone is the dramaturgy and the scene, punctuated by atmospheric music, some motifs, rhythmic figures, a varied musical language and orchestration including a percussion apparatus and objects that produce certain sounds. The music, the voice, plays second fiddle in importance, no longer moving us through the pleasing sounds of the voice but through effects; often poignant. Coloratura continues to make its appearance as in Ophelia’s mad scene, but instead of having a mad aria like in Thomas’s opera, we have a theater-operatic scene with disjointed coloraturas and great stage display, here Brenda Rae, soprano, is magnificent: not only with her forays into the high register, but in the manic coloratura (very different from Thomas’s). Scenically, it shows the psychological collapse of her character, from society woman to hysteria, half-naked, covered in mud and wearing her father’s tailcoat (an opera based on Ofelia would be worth it; surrounded by a macho world where she is at the mercy of what others decide).

Dean’s music isn’t easy on singers, even thankless at times; a splendid singer like Rod Gilfry, baritone, singing King Claudius, showed tiredness and vocal problems at the end of the performance despite a high-level characterization. Dean makes use of multiple layers of sound, contrasting dynamics, some obstinate cells, and surprising stylistic contrasts like the use of the accordion in the comedian scene. Sometimes I would have loved to find the irruption of song with a more generous or popular melody like “O vin dissipe la tristesse” that Thomas masterfully includes before the comedians’ scene. That would be my reservation about Dean’s “Hamlet”; it is an opera that works very well as a full-fledged musical play but does not survive offstage. Musically, too, Dean fails to rescue the poetry of certain original lines from Shakespeare’s play that Matthew Jocelyn uses in his libretto. This point is not minor and is one of the details that make me reflect on the validity of this opera versus other versions like Thomas’s or Faccio’s. In contemporary music there is very little disposition to reflect the beauty of a text: everything has to be tension, restlessness. On the other hand, the orchestral interludes, for scene changes, seemed to me to be of a high level; ideal for transitioning from scene to scene.

Allan Calyton sang a Hamlet that deserves all the praise for his constant appearance on stage. Clayton’s voice managed to tackle Dean’s difficult score, one that also requires an unusual stage commitment. His voice is a vibrant one, with supple, important sounds, that make me think that he will be ideal for German repertoire, including Wagner.

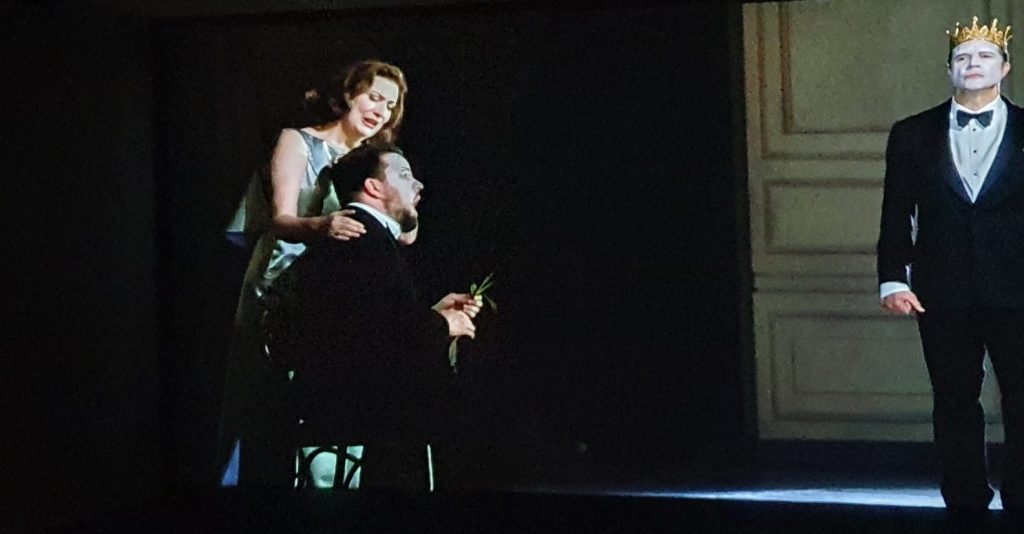

Sarah Connolly is a great mezzo-soprano and as Queen Gertrude she produced fine sounds and musicianship and her acting of the remorseful queen was spot on. As Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, countertenors Aryeh Nussbaum and Christopher Lowery were exceptional; often singing together or in canon and giving the work a comic contrast that Thomas’s score does not have. As Polonius, tenor William Burden also shone in his acting and singing; much more lyrical than some of the other singers in the production. Remarkable, also, were Jacques Imbrailo, a touching Horace, David Butt Philip’s powerful Laertes and John Relyea’s ghost. The latter is a splendid singer and bass-baritone; In addition to the ghost, he plays one of the comedians and the undertaker. This is part of the scenic conception and surreal touch since Relyea’s ghost doesn’t seem to be well differentiated from the other two characters. He also appears with the same white face, clown like, as most of the characters: this mime-like element perhaps is related to death (all the singers who are going to die or are dead have this feature). The opera, in the tragicomedy mold, leaves us with the question of Hamlet’s sanity. It is not always evident whether he is faking his madness or not.

Neil Armfield’s mise-en-scène (using some elements from previous MET productions) united the diverse elements of the play with a brilliant scenic pulse, including a complex final scene due to the duel of swords and the stage movement.

The MET Orchestra and choir, conducted by Nicholas Carter, presented the musical score in an ideal way: it made us pay attention to de diverse textures and effects (the score even asks the singers for some guttural singing; Ofelia sings while beating her chest); dynamic control was remarkable.

A musical theatrical experience that rescues in some way the original concept of opera (that of Jacopo Peri): more theater and recitative than a musical work. First the word, then the music. Does today’s public want to hear operas like this? It seems to me that if we have a repertoire of the greatest operas in history, these incursions into the contemporary are legitimate and help to have contrasting views of the genre and its development. However, I cannot help noticing that the Metropolitan Opera House was not full, that the final applause was more of a “success d’estime” than a triumph. Some singers where, deservedly, recognized by his work, particularly Ophelia and Hamlet. But it wasn’t thunder.

The musical difficulty and previous work of putting an opera of this nature makes it unfeasible to form part of a central opera repertoire, for example. The assistance of the people who went to see the live transmission was not large either. The MET, for the 2022-2023 season, is prescribing two other contemporary operas for digital transmission. This is an unfortunate decision. We don’t have the sophisticated public or a solid opera base worldwide – or in Latin America, for that matter – to dwell on titles that don’t appeal to a larger opera audience.

Nicholas Carter told me, in a conversation we had this week, that it’s okay if you don’t like a contemporary work at first, but continuous contact with it can produce interesting things. I realized that many people assimilated the concept of Dean’s Hamlet, after my introductory lecture where I presented the video and dialogue with Carter. Not everyone who attends MET broadcasts has this possibility, but I think the public, perhaps, is more receptive to the, new, to the contemporary, than some years back. Yet, its not a wide public.

It is important that we have access to what is done today, but along a healthy operatic repertoire that encompasses all styles. Music, and opera is an art of the present, as Jordi Savall would say; that is why it will never be a museum art. Dean’s “Hamlet” is a worthy example of 21st-century opera, but even so, there are contemporary operas more soundly based in the musical aspect.